Intimidation and violence could be used as tools of electoral corruption, but there were other means at the disposal of candidates. Research Assistant Sam Holden looks at one 1852 newspaper editorial and what it can tell us about the carrot and stick in mid-Victorian elections:

In 1852 a senior Government member was directly linked to a plot offering money for votes in Derby, while landlords demanded more than just rent from their tenants. An editorial carried by the Londonderry Times of 29 July 1852 lamented the corrupt state of British politics.

Elections during this period were particularly susceptible to “undue influence”.

In 1852, the year of this editorial, only one in seven males were eligible to vote, who owned or rented a property over a certain value (this varied throughout different parts of the UK). Constituency electorates therefore tended to be small, and margins of victory were often very slim. Each and every vote really did count, which made those with the vote possessors of something which could be extremely valuable in more ways than one.

Before the later Victorian period, there were no limits on how much money a political party or candidate could spend during an election. With the passing of the Corrupt Practices Act in 1852, this was the first election during which political parties were obliged to record their spending – but, with few checks in place, what was written on the balance-sheet might bear little or no relation to what was actually spent.

The author of the editorial suggests that this and other anti-bribery laws were full of loopholes the lawmakers could exploit – moreover, that they were deliberately included by self-interested MPs:

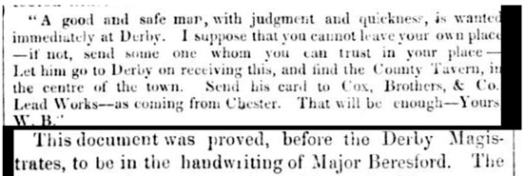

The author provides evidence in the form of a startling discovery made by police during the election in Derby, after searching a man on the street who was carrying bags of gold and bank notes (definitely less subtle than brown paper envelopes). They discovered the following note on his person:

The proven author of the note, Major (William) Beresford, was a Conservative MP. In fact, he had been, up to the election, both the government Chief Whip and the Secretary at War.

It must have been a remarkable discovery for the policemen to find a handwritten note from a senior member of Government recruiting someone to bribe voters!

The author also provides insight into the mechanisms of bribery; though perhaps exaggerated for sensationalist purposes, the description is as secretive a process as one would expect, though perhaps more elaborate:

Votes had a price, and the price of that vote could vary across the country by as much as twenty times. Factors influencing this could vary – one such elements could the stage and state of the election. If one or other candidates were but a handful of votes from victory, with the polls about to close, bidding among contesters for the few remaining uncast votes could reach the equivalent of thousands of pounds in today’s money.

In Derby, along with the handwritten note, police also discovered sealed moneybags designated for use in Shrewsbury. The relatively poorer constituency of Derby could be bought for less than more affluent Shrewsbury, as the captured briber Morgan explained to police while on his way to jail:

More broadly, the article also notes that elections in St. Alban’s and Sudbury had been declared void due to bribery allegations, and highlights a report in the Liverpool Albion which claimed the Conservatives spent £23,000 during the election there which is the equivalent of around £1.85m in today’s money: a very great deal to spend on one constituency! This is especially true, considering that the modern Conservative party spent around £18.5m on their entire campaign in 2017.

Major Beresford would go on to be censured by the House of Commons for his ‘reckless indifference to systematic bribery’, and was removed from his job as Chief Whip and Secretary at War. Interestingly, his successor as Chief Whip was also lost his seat on petition due to (among other things) bribery.

However, the author of the editorial did not consider this type of blatant bribery to be the most serious form of political corruption blighting the country. The real threat was thought to originate not from MPs like Beresford, but from the landlords:

Landlords wielded enormous power in determining the outcome of elections during this period, especially in rural seats which large numbers of tenant-voters. Unlike Major Beresford, they had more opportunity to motivate their tenants with the stick rather than the carrot.

The author details some of the ways a landlord could impose their political will on their tenants. They could send bailiffs to warn them against voting for disliked candidates, or they might personally summon and directly order them to vote for their candidate. Landlords might have the power to evict entire families if displeased with voting choices, or could retaliate by increasing rent or demanding arrears. On the carrot side, landlords could offer extensions on arrears or leases if they voted ‘correctly’. When votes were publicly recorded, those in power were able to confirm whether their wishes were met.

The author of the editorial therefore suggests that the introduction of the secret ballot would go some way towards improving the integrity of British elections:

The secret ballot was introduced in the UK with the passing of the Ballot Act in 1872, twenty years after the publication of this editorial. Eligibility to vote could be something of a poisoned chalice; the pressure many would have been under during elections could be enormous.

While election spending remains a contested topic today, universal suffrage and the secret ballot have long since become firmly-embedded parts of British elections. The conduct of the 1852 election can serve as a timely reminder of their value.

Sam Holden is a politics graduate of the Universities of Newcastle and Utrecht. Originally from Clitheroe, Lancashire, his academic interests include British political history, political philosophy and, more recently, electoral violence during the Victorian era.

(Sources: Londonderry Standard, 23 July 1852. Retrieved 2018, via British Newspaper Archive. Newspaper Images © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. National Archive Currency Converter. Guardian – Conservative spending on 2017 election. See also Robert Blake, Disraeli (1967))